A Light Unto the Nations: Barbara Steinmetz’s story of survival during the Holocaust

This Tuesday, in honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Barbara Steinmetz came to Centaurus to share her own story of how she and her family managed to survive the Holocaust.

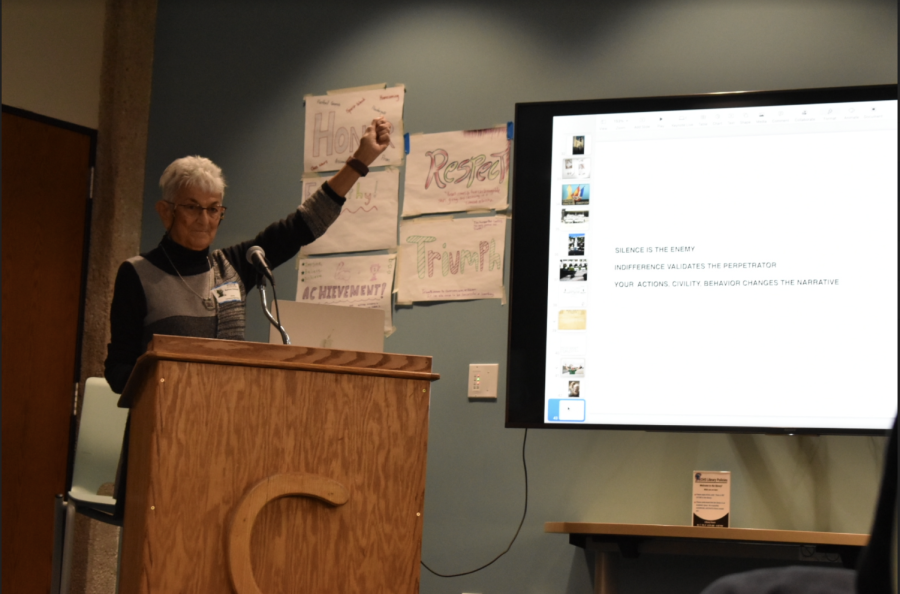

Barbra Steinmetz sharing her voice in the Centaurs High School library.

CW: This story discusses genocide and oppresion. Please Read at your own discretion.

Today is International Holocaust Remembrance Day. On January 27, 1945, Auschwitz, the largest of all of the Nazi internment camps, was liberated. This camp once held 1.3 million people: Jews, LGBTQ+ people, people with disabilities, Romani, people of color, and more. And yet, only around 7,000 walked out of the camp that day, most of them sick and dying; the rest had been tortured and killed.

The Holocaust was a genocide that worked to destroy the lives of millions of people. It was driven by antisemitism and racism, and was fed by fear. Hitler, who discriminated against those of the Jewish faith from the moment he came into power, saw the Holocaust as a way to finally eliminate Jewish people from Germany. During the Holocaust, Hitler’s power and ideas spread to many other countries, and Jews were forced to flee Europe, killed, or sent to concentration camps, like Auschwitz.

This Tuesday, in honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Barbara Steinmetz came to Centaurus to share her own story of how she and her family managed to survive the Holocaust. Steinmetz was born in Hungary in 1936 in the midst of growing antisemitism. Soon after, they moved to Italy where her parents ran a hotel until Mussolini stripped them of their citizenship in 1938.

In 1940, they fled the country and Steinmetz’s father began to desperately search for a place that would take them. He wrote to twelve countries -including the United States- begging for safety for his family, but no one would take them in.

At the same time, Steinmetz, her sister, and her parents returned to Hungary to try and convince the rest of their family to leave, but their relatives didn’t believe their claims of what was to come. How could a country they had lived in for generations turn on them? How could their friends betray them? They didn’t listen and chose to stay in Hungary.

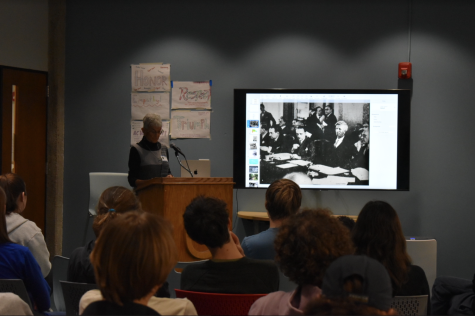

In 1938, as Jewish refugees were fleeing Europe and the Holocaust, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called the Evian Conference to show America that he was taking action and finding a solution to the millions of Jewish refugees. Thirty-eight countries attended. Only one offered asylum: the Dominican Republic.

Rafael Trujillo ruled the Dominican Republic during World War II. At the Evian Conference, he offered to take 100,000 refugees into his country; mostly young white men that could marry his citizens with darker skin in hopes of breeding a lighter skinned population. Years earlier, this racist dictator had massacred thousands of Haitians. His motives were evil and twisted, but by allowing Jewish refugees to enter his country, he saved Steinmetz and her family.

Life in the Dominican Republic was not easy. Jewish immigrants arrived in Sosúa, and had to build their own houses. The conditions were horrible. Steinmetz remembers sleeping under a mosquito net and having to shake the bed sheets every night before bed to make sure there were no tarantulas hiding in the folds of the blanket. The bathroom was a crumbling shack. Each day was full of hard labor. Life in the Dominican Republic was so unlike life in urban Europe. Jewish immigrants experienced culture shock as they interacted with people that were very different from themselves and adapted to this new life.

There weren’t many schools in the area, but education was very important to Steinmetz’s parents. They were able to enroll their daughters in a Catholic boarding school, but there were multiple conditions. Only the Mother Superior of the school knew Steinmetz and her sister’s true identities, so the girls had to pretend to be Catholic. They took part in religious ceremonies and prayed the Rosary for the four years they attended the school.

Then, when Steinmetz was nine years old, her parents came and picked her and her sister up from school. They had the opportunity to immigrate to America.

When Steinmetz’s family arrived in America, her parents were hired to wash dishes in a hotel. They did not know any English. They weren’t allowed to have their kids with them, and so Steinmetz and her sister were sent off to summer camp. Steinmetz remembers leaving her parents; she and her sister were crying. They were alone in a new country and couldn’t understand anything anyone was saying.

The summer camp was a blessing. The kids at camp helped them learn English, and so they were able to start school in the right grade levels in the fall.

Now, Steinmetz lives in Colorado. She has shared her story with many people: schools, churches, students.

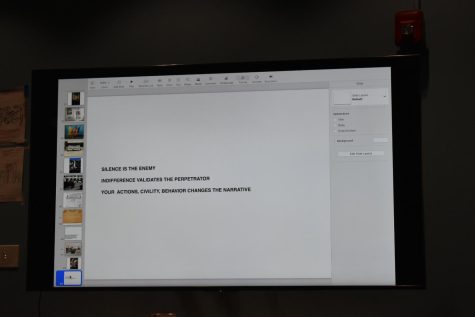

Throughout her talk, Barabra Steinmetz emphasized one idea: “Silence is the enemy.” She recounted how fear had fed Hitler’s agenda and allowed him to stay in power. Steinmetz emphasized the power of one’s actions and voice.

“Everybody’s got a story,” She said. “And everybody’s got to write it down.” We have a duty to pass our story along, share it with the world, with the next generation. “The only way we can change, that we can learn, is if we are each other’s partners.”

American democracy is not all that different from democratic Germany. Many of the ideas that led to the Holocaust still exist today: “We could easily have- look at all the racism that’s going on.” Steinmetz remarked. “[Racism] has been the driver of much of what’s going on, you know. It’s the driver, and the fear.”

To sum up Steinmetz message: we have to look at history, at what happened during the Holocaust, in order to learn from it so we can prevent horrors like this genocide from ever happening again. And, it’s our responsibility to pass these stories on so that others can learn too.

At the end of the day, it is up to us to stand up for others and enact change. “My message isn’t my story,” Barbara Steinmetz concluded. “My message is to be a light unto the nations.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Centaurus High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Sophie Lewandowski (she/her) is one of the junior editors, as well as a reporter for The Warrior Scroll. She is a junior at Centaurus. In her freetime,...